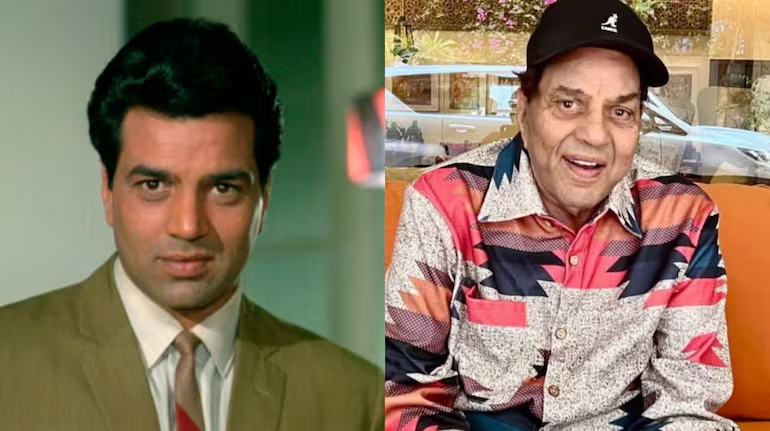

Dharmendra: The Strength of Softness

In the crowded mythology of Hindi cinema, Dharmendra stands apart, not merely as the “He Man” of the screen, but as its most quietly enduring heart. For more than six decades, he has inhabited the Indian imagination in ways that are less about stardom and more about sentiment, the moral geography of a nation that once believed gentleness was not a weakness.

Born Dharam Singh Deol in Punjab’s Sahnewal in 1935, Dharmendra arrived in Bombay during the years when cinema itself was shifting tone, from the idealist austerity of Nehruvian narratives to a more sensuous, conflicted modernity. He was discovered through a Filmfare talent contest, but his real discovery happened onscreen: the way the camera loved his stillness, the way emotion flickered across his face without artifice.

Before he became the icon of muscular masculinity, Dharmendra was the face of vulnerable men in Bandini, Anpadh, Anupama, and Satyakam. These films, with their moral tremors and silences, drew on his gift for understatement. He did not perform pain; he contained it. In Satyakam, Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s most morally charged film, his character’s idealism decays under the weight of a corrupt new India, and Dharmendra inhabits that decay with a rare purity. It remains one of Hindi cinema’s most ethical performances, a portrait of the good man crushed by his own goodness.

Yet, to reduce Dharmendra to solemnity would be unjust. His genius was that he could hold both tragedy and charm, rage and humour, in the same breath. In the 1970s, when action cinema became the new grammar of the screen, he transformed himself without losing that interior tenderness. His Sholay’s Veeru was a man of muscle, but also of mischief, his bravado balanced by an almost childlike vulnerability. This duality became his signature. Unlike Amitabh Bachchan’s brooding rebellion or Rajesh Khanna’s romantic fatalism, Dharmendra’s hero carried no irony. He was emotionally transparent, an ordinary man with extraordinary decency.

What made Dharmendra special was his refusal to shed his rural sensibility even as he navigated the industrial machinery of Bombay cinema. His Punjabi earthiness, the accent, the smile, the casual dignity, gave him an authenticity that urban glamour could not mimic. When he spoke, it was less dialogue and more reassurance, a language that told the audience, I’m one of you.

That identification ran deep, especially for post Independence Indians who were watching their villages and values being transformed by modernity. Dharmendra’s heroes, honest policemen, idealistic engineers, wounded lovers, seemed to carry the moral residue of a simpler world into the chaos of new India. He made sincerity fashionable before cynicism became the default setting of success.

In private life too, his persona echoed this negotiation between ideal and imperfection. His marriage to Hema Malini, his complex family life, his eventual retreat into poetry and quiet reflection, all became part of his public myth. But what endured through it all was his sehj, that Punjabi calmness, the ability to laugh at himself, to age without bitterness. His occasional appearances in films like Life in a… Metro, Apne, or Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahani were not nostalgic returns but gentle reminders of continuity, that certain presences never vanish, they just mellow.

If one were to read Dharmendra not as an actor but as a text, he would be a document of Indian masculinity in transition. From the stoic moralist of the 1960s to the swaggering action star of the 1970s, and now the tender patriarch of the present, his journey mirrors the country’s own emotional evolution, from idealism to assertion to introspection. In an age when heroes have become loud, he remains the exemplar of a vanished decency, the strength of softness.

Even today, when he appears onscreen, his eyes moist, his voice cracked by time, he seems to bring with him a fragrance of an older cinema, when truth was not performed but felt. Watching him is to remember that acting, at its best, is not mimicry but presence, and that some presences, like Dharmendra’s, belong less to cinema than to the collective memory of a people who once believed in goodness.